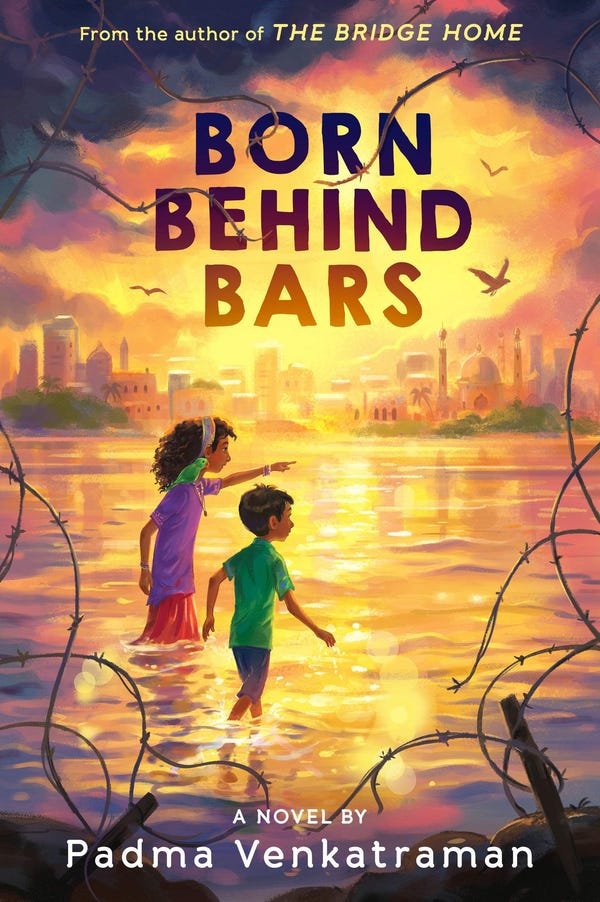

Process Talk: Padma Venkatraman on Born Behind Bars

Photo by Franca Cirelli. Image courtesy of the author

I’ve been meaning to talk to Padma Venkatraman for a long time. Padma is the multi-talented author of Climbing the Stairs, The Bridge Home, A Time to Dance, and Island’s End, and a former oceanographer who brings the richness of her life experience to her work.

This lightly edited transcript is drawn from our conversation.

[Uma] I loved how Born Behind Bars shows the complexity of religious, linguistic and cultural differences in India, even while the narrative cuts straight to the heart of what it means to be a child. Talk about this book. What does it means to you?

[Padma] It has been long in the making. I started it in 2013, when I heard a BBC news report of this woman who had been stuck in jail because she was too poor to post bail. There was no discussion of whether she was innocent or not, but she was of a low caste as well, and she was left in jail for longer than if she had been convicted of a crime. She had a child. To see this little boy’s face and to know he had been born in jail and was then kicked out and his mom stayed behind—it left this deep impression on me. From that root of a real story it became what Born behind Bars is.

One person whose poetry and philosophy has been really important to me is Kabir. You would know—I read Tagore’s translation of Kabir’s poetry.

[Uma] Songs of Kabir—yes, on the cusp, right? Not Hindu, not Muslim, but both.

[Padma] Yes, when I was quite young. In fact, I have the book still, sitting over there. Having been exposed to the philosophy and poetry of this amazing person—as soon as this kid appeared, I knew he would be called “Kabir.” I knew why there had been so much strife, why his mother was alone in jail, why his dad hadn’t helped out, why they had been sort of forgotten not only by society but also the family. I just heard Kabir’s songs being sung in my head and it all came together for me.

[Uma] I’m going to quote you a passage:

“One of my saddest thoughts is maybe Appa stopped writing because he stopped caring about Amma.

“But whenever that worry enters, I drive away as fast as I can, just as you have to chase away an ant as soon as you spot it. If you don't, they invite others to join them. And soon you have an endless line of sad thoughts chewing at your heart.”

How did this character grow for you as you wrote the book?

[Padma] In little spurts. Every once in a while, I would hear something that he said and I would write it down. And then, actually, during the lockdown, he came to me, because, you know, people were saying, “Oh, it’s like being in jail, we’re locked in, we’re stuck.” And to suddenly made me think, No-no-no, wait. It is, but it also totally isn’t.

Metaphors like the ant I think come naturally to me because I grew up in India and the setting is so full of these small things.

[Uma] What about that prison setting?

[Padma] Years ago, when I first began to work on this book, I sent a draft to a friend of mine who works in a women’s prison [in the US] to get feedback. There’s a place in the book where he’s always looking at angles and the only thing he sees above are the clouds. And one of the women had written, Yes, I love this. That’s all I see out of my window!

But in a way, although there was so much going on in the States that resonated with this book, I knew I wanted to set it in India. And I also read Kiran Bedi’s book about Tihar Jail, and the terrible conditions even though there were efforts at jail reforms.

[Uma] So there’s a particularly colorful, quirky metaphor that I wanted to ask you about, and I’m sure no one else is going to ask you about this, but it’s the kili josyam (கிளி ஜோசியம்), with the fortune-telling parrot. Such an iconic bit of street life. Where did that come from?

[Padma] There was this wonderful man who was once upon a time our gardener, back when we had a huge house, and then when we lost everything, he still stayed with me and my mother. He was very much a part of our lives. He once took me to see one of these people. I didn’t understand a thing but it was so exciting for me to see. I was impressed because that little bird didn't have any kind of cage that I could see. Sometimes I see people with a monkey in a cage and that would always upset me but this little bird was just hopping about, picking out cards.

Another time I was walking on the IIT campus, which is so full of trees, and my brother, who’s much older than me, saw these birds attacking something. He walked up and saw this tiny mynah bird.

Padma told me that her brother brought the injured bird home. It stayed with Padma for a while, perched on her shoulder and even began to mimic human words. So the bird in the story was created from these two experiences. This is how fiction grows—you take a snippet from here and one from there and soon it’s becoming its own reality.

More to come from Padma on her choices of structure and form in Born Behind Bars.