Guest Post: The Gift of Fire by Lola Opatayo

Lola Opatayo is a crafter of words and the host of a generous, welcoming literary podcast, Journey of the Art, on which she invites writers and storytellers to talk about their art.

I asked her to write about what she gets out of creating space for others’ writing. Here’s her piece on one of her interviews, a lovely meditation on what happens when you refuse to treat this writing business as a competitive sport:

The Gift of Fire

by Lola Opatayo

When I logged on to speak with Radha Chakravarty for Episode 24 of my podcast, I was immediately arrested by her calm disposition. Her burgundy scarf complemented the calm in her brown eyes as she softly asked if I could hear and see her clearly. It was 6:30 am in Delhi, where she lives and works, and I suspect she feared that the dawn was casting a gloom over her face. Little did she know that she herself was the light and that she had come to alter my life in a special way.

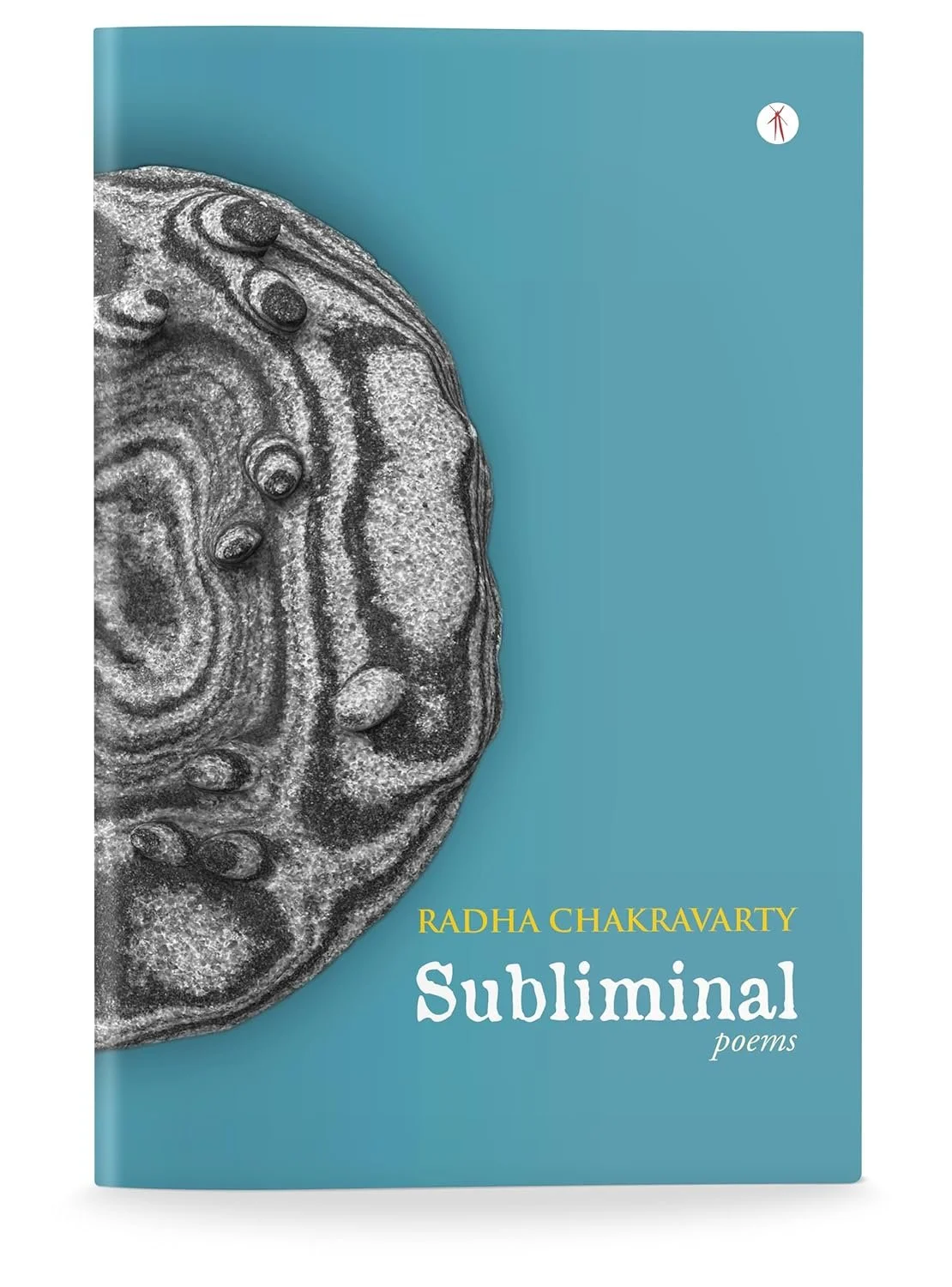

I had come to know Radha through another guest on the podcast. Over the next few weeks, we exchanged messages about her latest work, Subliminal, a poetry collection on the pandemic, feminism, and reflections on human relationships. Radha is also a scholar and translator, who has famously translated the works of Rabindranath Tagore and Mahasweta Devi, amongst others.

As soon as I asked her my first question, I knew this was going to be one of my favourite interviews. Listening to Radha was poetry; every sentence carefully structured to deliver substantial meaning and insight. She spoke about how being bilingual set the stage for her future work as a translator and the importance of getting in the skin of a writer’s work. This phrase, getting into the skin of a writer, opened up a new world of meaning for me as I wondered what stories I might retell or translate from the folktales I grew up hearing and reading. This new world of meaning was Radha’s gift to me. They don’t know it, but all my guests bring me a gift of insight, and this one was the key I’d been searching for.

In 2020, during my residency at MacDowell, I had stumbled on and began to execute the idea of retelling these inherited tales as a means of preserving them from the whirlpool of Western tales. It had been years since I last worked on the project, and this idea of envisioning a story through the eyes of the storyteller offered a new perspective through which I could approach these stories.

This perspective was crucial to me because I’ve been battling with what most would call a writer’s block. For several reasons, both personal and professional, I had stopped writing creatively and had come to a point where my storytelling voice had become a distant memory.

As a translator, Radha talked about the distinctive quality of the translator’s voice and its importance in interpreting a work that offers a fresh meaning for the current world. And although she herself feels a certain fear of inadequacy when taking on these projects, she recognizes that translation is an adventure, a bold step towards bridging the gap between the past and the present.

I come from a culture of oral storytelling traditions. Under the moonlight, the spirit of a folktale inhabits the narrator (usually an elderly relative or close family friend), and children are transported to a magical place where turtles fly and lions sing. But with colonial influence and a forced immersion into western storytelling, the magic has lost its power. The children of my home country seem to be more enamored with faraway tales than the stories in their own backyard. And the narrators? Silenced and subdued by redundancy.

The past cannot be influenced, but the present and the future we can control. So I decided to bring these folktales to the fore by retelling them, in the hopes that they can mingle with the faraway stories and be received by today’s children. This is no mean feat. The old stories must connect to the language and style of the present time. I believe this understanding is what set Radha on an adventure to bring the worlds of the past and the future together through translation.

Now I see that it is this adventure that has eluded me and prevented me from writing for the past five years. For the writer, adventure is surrender, a giving up of carefully constructed plans for the supremacy of the story (the way and manner it wants to be told). I lost sight of this. I wanted to control all the outcomes, and when my plans failed, writing ceased to be an act of joy. Recently, this truth became even more evident in a conversation I had with myself.

Q: When did writing stop becoming fun?

A: When you started expecting too much of it.

Q: Why did I expect too much of it?

A: [redacted]

Q: What should I expect of it now?

“I think if we can transfer the form of our past from one generation to another, we can fill up the cracks with the present so that the future is a robust personification of who we are.”

A: The only expectation you should have of your writing is that it should speak to you, affect you. It is like the wind. You cannot affect/capture it, rather it affects/captures you. The adventure of the writer is allowing the wind of words and ideas to blow as it wishes. To tussle your hair and whip up your skirt. To slam doors shut and bend trees.

Although she did not say so, it seemed to me that Radha had accepted a sacred duty: to interpret some of the literature of her people so that people from other places and experiences can have access to them. It is what I would call a duty of transference.

I believe this duty falls on some of us. It is a duty that surpasses preservation because nothing truly stays the same. Things evolve, and cultures do too. I think if we can transfer the form of our past from one generation to another, we can fill up the cracks with the present so that the future is a robust personification of who we are.

Radha’s scholarly work covers feminism, representations of the body, and feminist literature. In her poem, “The Severed Tongue,” she pays homage to Khona, a legendary Bengali astrologer and poet whose tongue was severed to silence her brilliance. When I asked her how much progress she could say her community had made in this regard, she pointed towards the rich literature of and by women that have existed and continue to exist as “an alternative space” where the articulate questioning of societal events can take place.

“Words and silence [are] very central to one’s awareness,” she said with a gentle smile and then spoke about “the tension between silencing of different kinds and the need to speak out.”

In the context of my writer’s block and the expectations I placed on my writing voice, I can’t help but see my inability to write and my aversion to adventure as a silencing of sorts. As the world becomes more polarized and the threat of going viral for the wrong reason (and getting “cancelled”) hangs over one’s head like a heavy fog, adventure becomes a precarious prospect. In many ways, the artist is now compelled to toe the path of least resistance and less imagination.

As our wonderful conversation drew to a close, Radha talked about a “sharp shift in perspective” and the invitation of the stars to a sense of purpose that exceeds our present circumstances. In other words, what legacy will our actions (and words) leave behind?

This, for me, was the frosting on this unexpected cake. In the last few weeks, echoes of my writing voice have begun to caress my ears and clusters of words and imagination have deposited themselves in my mind. This conversation with Radha has lit a fire in me so that now, when I ask myself why I must write, I remember the invitation of the stars. I remember the sacred duty of transference, which I sense has fallen upon me too.

Radha is now retired and spends her time travelling around the world with her astrophysicist husband. She talks about her balcony garden and how proud she is of it, and I know that when I’m as old as she is, I want to have toed the path of my duty, refusing to be silenced by my own self.