Process talk: Amy Alznauer on The Boy Who Dreamed of Infinity

I don’t even remember when I first heard about Srinivasa Ramanujan, the groundbreaking and intuitive mathematician, so I must have been very young. In India, his birthday, December 22nd, is now celebrated as National Mathematics Day.

Photo courtesy of the author

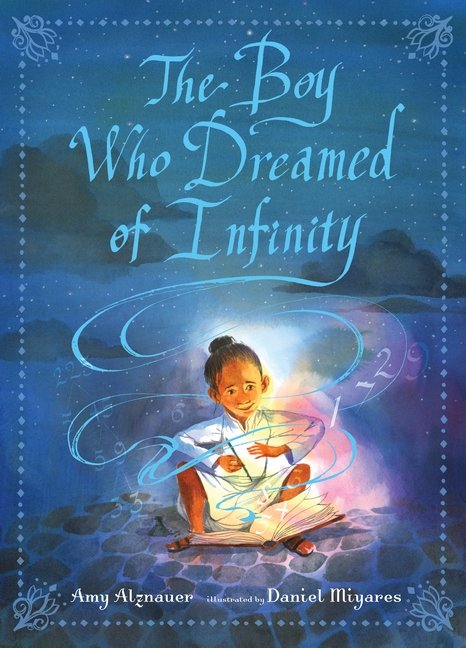

I read Robert Kanigel’s biography of Ramanujan years ago and very much hoped that one day, someone with facility in both math and language would write a children’s book about his remarkable journey. I’m so thrilled to see what Amy Alznauer has done now in her picture book biography, The Boy Who Dreamed of Infinity. I’m delighted to speak to Amy about her beautiful book..

[Uma] Ramanujan’s story is so complicated. It spans the world, delves into vast concepts, opens up questions far into the future—and yet his quest was so deeply personal. How did you manage to pack so many complexities into the small container of a picture book? Where did this text begin for you and how did it become what it is now? How did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

[Amy] In some sense this book has been a lifetime in the making. The story started for me before I can even remember. There’s a little home movie of me as an infant, propped up in a 70s orange office chair watching my father at the chalkboard passionately explaining the Rogers-Ramanujan identities. This was five years before he discovered the lost notebook of Ramanujan in a Cambridge library. This was long, long before I started studying Ramanujan’s mathematics and life myself. But even after I decided I wanted to tell this story it went through many permutations. First, I thought I’d tell the story of the lost notebook as a kind of mathematical memoir, but eventually, after having my own children, I became convinced it should be a story for children. This was my first picture book bio so the many initial versions all sounded like they were written from a great distance. It was only after I centered in on the driving metaphor – small and big – that I was able to really tell the story I wanted to tell. The words small and big managed to encapsulate so much of Ramanujan’s life: the smallness a child feels in the great world, his spiritual beliefs, and his mathematics which was often caught up in questions of the infinitely large and the infinitesimally small. This metaphor also provided a movement or plot, the crescendo of a child growing up, the risk of taking one small step that will launch you into your future. That’s why I am so in love with Miyares’ final illustration of the great steamer under the night sky – it so beautifully conveys those feelings and realities of small and big.

Copyright © 2019 Candlewick Press. All Rights Reserved.

[Uma] You’ve integrated Tamil words into your text in an intimate, loving way. Everything’s clear in context and no glossary is required. This is so unusual for a writer who comes to a story from outside her subject’s cultural and linguistic background. I see from your acknowledgments that you had help with Tamil words and sounds. Can you talk about that process?

Fire extinguisher buckets, labeled in Tamil and English, in Ramanujan’s old school in Kumbakonam, Tamilnadu. Photo courtesy of the author.

[Amy] Well, I wanted this story to feel intimate and authentic, so I spent time in India and then I worked extensively with Indian mathematicians, biographers of Ramanujan, and native Tamil speakers to get everything right. It is so gratifying to hear that you think we succeeded! In particular, I worked with Kumar Sambandan, a native Tamil speaker and someone who has been involved in teaching Tamil to second generation Indian-American kids. I asked him not only about the meaning and transliteration of Tamil words, but questions about Hindu stories and rituals and how certain sounds – the call of goats or the fluttering of bats – might be conveyed with Tamil syllables. He beautifully suggested pada, pada, pada for the fluttering wings, which sadly didn’t make the final cut. Through these conversations I worked not only to get the words right but to gain a deeper familiarity with Tamil domestic life. For example, Kumar told me that there’s an iconic Indian scene or image of mother and child: the mother holds her child (or rests the child in a sort of saree-made cradle) and points up at the stars and moon. This became the opening moment, when the reader first meets Ramanujan.

[Uma] Yes, the thule thottil or cloth cradle (துலே தொட்டில்) is an iconic, loving image from my mother’s generation and earlier. There’s this clear sense in the culture of reverence for babies that comes through in these pages. In all, love is writ large in this book, embodied in the author’s note with poetic, moving lines like this one: “Every morning when Ramanujan woke, numbers rose with the sun and spread to every corner of his mind.” So my question is, was it love of mathematics that supported and empowered you to write this story, or was it something else?

Copyright © 2019 Candlewick Press. All Rights Reserved.

[Amy] What a lovely comment! Thank you, Uma. I do love mathematics, but even more I love my father who loves mathematics with a passion that people usually only associate with artists or mystics. When I was little, I generally found math boring and pointless in school, but even then I still knew that there was some hidden power and majesty in mathematics. I grew up in a house where I could feel that powerful beauty brewing in the basement, in my father’s tiny office under the stairs. I could smell it brewing in the coffee he drank as he worked and in the strong blue ink he used to write all those pages of symbols I didn’t yet understand. I could hear it in the sound of him bounding up the stairs two at a time to announce to the family that he’d done it – discovered something new, proved a theorem. It was that sense of the mystery and adventure of mathematics that I wanted to convey more than anything else, for Ramanujan was not someone who learned mathematics or even learned to love mathematics in school. He played with numbers on his own for the sheer joy of it.

[Uma] Every book teaches a writer something she didn’t know before. What did writing this book teach you?

[Amy] Until I wrote this book, I hadn’t yet figured out what kind of beast the picture book biography is or even what my approach to this beast might be. And it occurs to me right now that I’m calling a book a beast because to write one you have to in some sense tame it, in that Little Prince sense of falling in love with the story, of seeing the story as “unique in all the world” and then becoming responsible for it. I learned that a picture book biography only comes into focus for me after a quest to locate the adult in the child, to find out what questions, what passions, what images and stories were already present for the child (in their dreams or games or pursuits) that might predict or prefigure their eventual path. I find this approach so fulfilling because it takes me not only to the luminous ground of the subject’s childhood but also to my own. I think childhood is where most stories are born, but I’ve been able to see this in a more literal way through writing biographies.

[Uma] Amy that’s remarkable—"seeing the story as ‘unique in all the world’ and then becoming responsible for it.” I’m saving this for myself. It’s so rich and so vital. Thank you so much for talking to me, Amy Alznauer!