Process Talk: Caroline Carlson on The Tinkerers

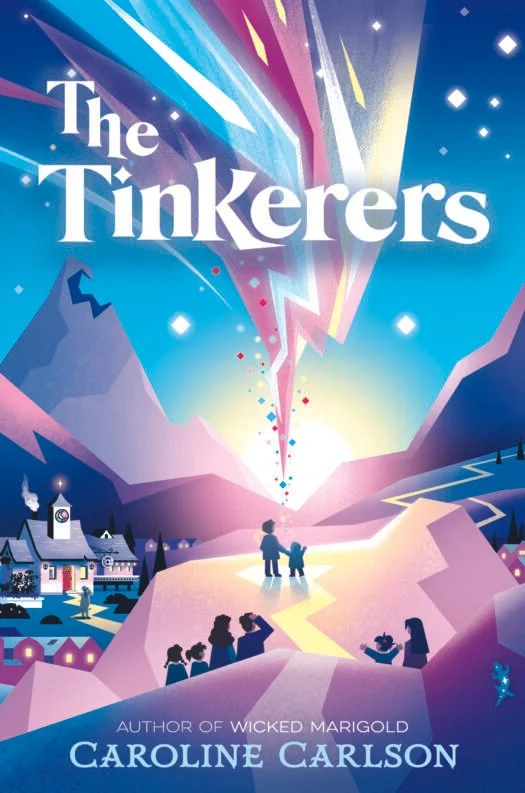

Stargazers Valley is an isolated village where Peter, the young protagonist of The Tinkerers, gazes at stars, listens to stories, and tries not to step on star-eating newts. Peter lives an ordinary kid life in a rural, mountainous setting with astromancers and a magical aurora that is the subject of study. Then strangers arrive, and things get strange. It’s a weirdly wonderful book, funny and unexpectedly touching, and its family and community context is one of its charms. I asked Caroline to tell me more about The Tinkerers.

[Uma] Mom says, "Life's a lot more complicated than a star tale, right?” Talk about the complications you lean into in this story.

[Caroline] You’ve read my previous novel, Wicked Marigold, so you’ already know that I’ve been interested lately in playing around with familiar storytelling forms. Wicked Marigold is a fractured fairy tale that asks questions about whether the stories we tell about our own lives can always be neatly organized into good versus evil and heroism versus villainy, with a happily-ever-after moment at the end.

My new novel, The Tinkerers, is outwardly very different from Wicked Marigold, but I think of the books as thematic siblings, because I’m still asking many of those same questions about storytelling. How do we tell the stories of our own lives, and is there only one right way to tell them? The Tinkerers begins with an essay that the protagonist, Peter, has written about an evening he spent stargazing with his family. It’s full of pretty language and pleasant sentiments, and it wins Peter a prize in a writing contest—but readers learn over the course of the book that the events in Peter’s essay are only part of what happened that evening, and the other events, which are less pretty and pleasant, don’t fit neatly into his prizewinning narrative.

Peter is a kid who likes neat stories with happy endings. He likes his village’s star tales, or folk tales, with their clear messages and obvious villains. And he works very hard to make sure that he’s always one of the good guys in the story of his own life. But he’s also a twelve-year-old who’s becoming more aware of his world and its moral complexities, and he’s beginning to realize that it’s hard to be a kid who always does the right thing when there’s not always one right thing to do.

[Uma] You say in your acknowledgments that it took you a long time to tell this story right. We only persist this way when we’re writing books of the heart. What makes this a book of your heart?

[Caroline] At school visits, kids often ask me if I’m like the characters in my books, and I usually say that I’m not particularly similar to my protagonists. But Peter is an anxious kid, which is something I know a lot about. He’s very good at being good, and he has an almost magical belief that as long as he doesn’t make any mistakes, everything in his world will be okay. If he does make a mistake, who knows what might happen? He’d rather not find out.

I spent my childhood holding onto the same magical belief Peter has, and it wasn’t until I was an adult that I came to understand that even if I did everything in my life perfectly, something bad could still happen. I was almost giddy when I realized it. Not everything awful in the world was my fault! I wished I had been able to understand that years earlier—and I also thought it was an interesting premise for a story. What if a kid who hates making mistakes finds a magical device that he can use to turn back time so that his mistakes never happen? Theoretically, with a device like that, he could turn his own life into a perfectly neat story with a happy ending. But I had a feeling that things wouldn’t work out quite that way for him.

[Uma] This is a story about power and power structures, big issues tackled with lightness and humor for a readership whose own power and agency is limited and under adult control. Why does this matter and why does it matter now?

“If we have tremendous power, how should we use it? And if we don’t have tremendous power, how can we still make positive change in the world? This second question is particularly important to me because I think it’s one that lots of children and adults share right now. ”

[Caroline] You’re absolutely right that The Tinkerers is about power and control, but what’s interesting to me is that I didn’t set out to write it that way. When I started writing, I was most interested in exploring Peter’s anxiety on a character level. But Peter’s anxiety is deeply connected to his desire to control every aspect of his world, so writing about anxiety turned out to mean writing about power and control. On top of that, there’s genuine magic in the book, and writing about magic always leads to questions about what the magic can do, who has the power to use it, and what they’re going to do with that power. It turned out that I couldn’t write about magic or anxiety without writing about power, and once I realized that, I started to explore the topic more consciously.

I would say that The Tinkerers is interested in two related questions: If we have tremendous power, how should we use it? And if we don’t have tremendous power, how can we still make positive change in the world? This second question is particularly important to me because I think it’s one that lots of children and adults share right now. We want to change our world—to improve our air and water, to keep the people we love safe from violence, to ensure that all of us can live happy and healthy lives. But we don’t always know what we can or should do to make these changes happen. Should we write polite letters to our government officials? Should we try to change the minds of people who disagree with us? Should we care for our own families and give them the best life we can? Should we get out in the streets and protest? Should we pursue civil disobedience or even more drastic action?

The characters in The Tinkerers are living under a colonialist, surveillance-heavy regime. They each have different answers to the question of how to make effective change in their society, and they disagree about whether making change is even possible or necessary. The book doesn’t attempt to resolve these disagreements, because I don’t think there’s a straightforward or obviously correct resolution. I hope, though, that young readers will pick up on the question of how to make change and consider what their own answers might be, because thinking about complex questions in fiction is excellent practice for thinking about similar questions in real life. I also hope that young readers will notice the moments in the book when kids do have the power to make change—not through magical means, but by sharing their thoughts, being silly and creative, or even breaking the rules.

[Uma] The Tinkerers is structured in short snippets, its scenes and accounts of myths (in Peter's first person viewpoint) alternating with clips from surveillance cameras, newscasts, logs and briefing books maintained by the all-seeing imperial authorities, and more. What made you decide to tell the story this way?

[Caroline] The simplest answer is that it’s tremendously fun. I love playing around with form, trying out new writing styles, and puzzling over how to weave lots of different storytelling documents together into a narrative that makes sense.

A more technical answer is that those documents allow me to get around the limitations of my first-person narrator. Peter, who narrates most of the book, can only tell readers what he knows, and even at the end of the story, he doesn’t have all of the information that readers will need to fully understand what’s happened. I use documents to give readers that missing information and help them put the pieces of the story together.

And the thematic answer is that I like how the documents underline the idea that there is no single, objectively correct story here, no definitive explanation of how the book’s events unfolded. Each character would tell this story a little differently if they had the chance. Even the surveillance camera transcripts, which are supposed to be objective, are transcribed by a person with her own particular point of view.

[Uma] Linnet says, “If you feel uncomfortable, I've done my job.” How do you see the role of art and of creativity in general, in speaking the truth and refusing to be silenced?

[Caroline] Art has always been used to communicate big ideas about society, and those big ideas are sometimes unsettling. It doesn’t always feel pleasant to sit with a book or a painting or a piece of music that presents us with an unfamiliar argument or a perspective that’s different from our own. Some people try to ban, destroy, or hide art that makes them uncomfortable, but they forget that discomfort isn’t necessarily a sign of harm or damage. It can also be a sign of growth.

That said, my artistic philosophy is a little different from Linnet’s. Linnet’s version of social commentary is painting a huge mural of the empress as an eight-headed green monster on the wall of her school; she wants to be shocking and provocative in her art. But I think there’s also something to be said for art that makes you feel comfortable even as it speaks its truth and gives you new ideas to think about. My publisher has described The Tinkerers as a cozy fantasy, and that coziness is absolutely purposeful: I want my audience to feel wrapped in the warmth of the story world as they read. I want their journey through the book to be delightful and magical. And I hope that as they experience that magic and delight, they also start to ponder some of the questions that the story explores.

Truth doesn’t always have to be shouted to make its point or reach its audience; it can be sung joyfully, too. I think that both philosophies of art-making have their strengths, but since I’m a children’s book author, I prefer delivering my truth to young readers with as much joy and comfort as possible.

[Uma] Starstuff, with its intriguing colors and its effects on the world—talk about how that became part of the story.

[Caroline] I’ve written six fantasy novels now, set in four different fantasy worlds. And every time I start writing a book that’s set in a new fantasy world, I groan a little, because I have to create a new magic system that’s not only semi-coherent but also different from the other magic systems I’ve built in the past. When I started writing The Tinkerers, I knew that I wanted the time-reversing device in the book to be powered by some sort of magical substance, but I wasn’t sure what that substance should be.

Then I thought about all the videos I’d been watching of the northern lights. This was during the height of the pandemic, when I didn’t leave my house much but spent a lot of time as an armchair traveler, watching YouTube videos from around the world. I was particularly captivated by clips that content creators in the far north had shared of the aurora borealis, which I think is one of the closest things to magic that exists in our real world. It didn’t seem like it would be too hard to nudge that almost-magical phenomenon completely into the realm of the fantastic. In The Tinkerers, the aurora is called the Southern Skeins, and it’s made of a luminous, multicolored material called starstuff.

The idea of starstuff was particularly appealing to me because it fit well with some of the story themes I’d already been exploring. Starstuff is part of the natural world, and it can’t truly be controlled by humans. It’s wild and beautiful and valuable and dangerous; it makes people anxious; it makes people wonder. No one in The Tinkerers has all the answers about what starstuff is or how it works, but they can tell a thousand stories about it as they try to understand.

Wild and beautiful and valuable and dangerous—I love that, Caroline! Thank you for this conversation.