Process Talk: Leslie Booth on writing A Stone is a Story

“For me, geology is so much more than facts about rock types. It’s also about transformation, resilience, and the immensity of time. ”

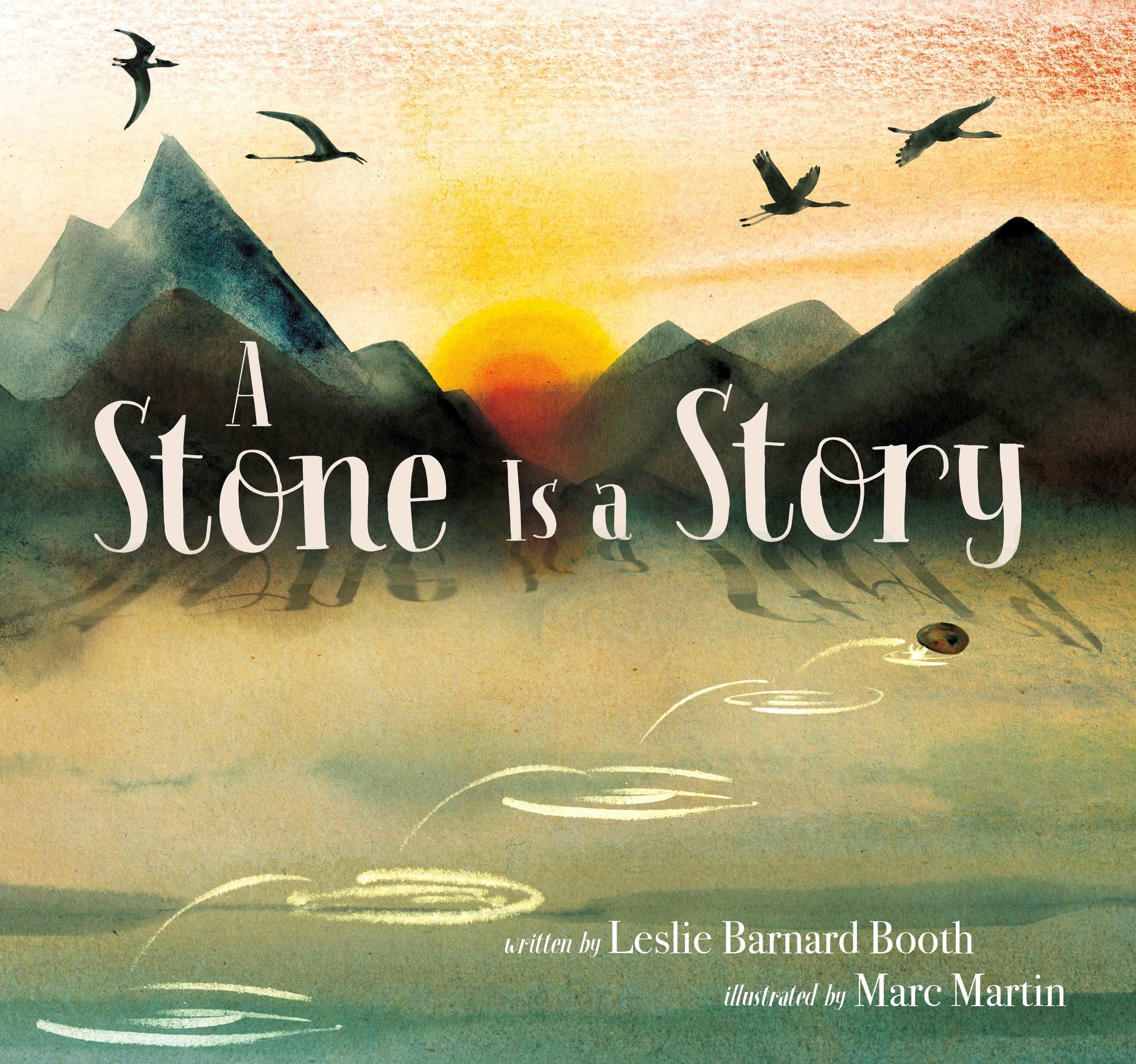

In the manner of Marion Dane Bauer’s The Stuff of Stars, here is a picture book about time and matter. I invited author Leslie Barnard Booth to tell me more about the creation of this book.

[Uma] What made you want to write A Stone is a Story?

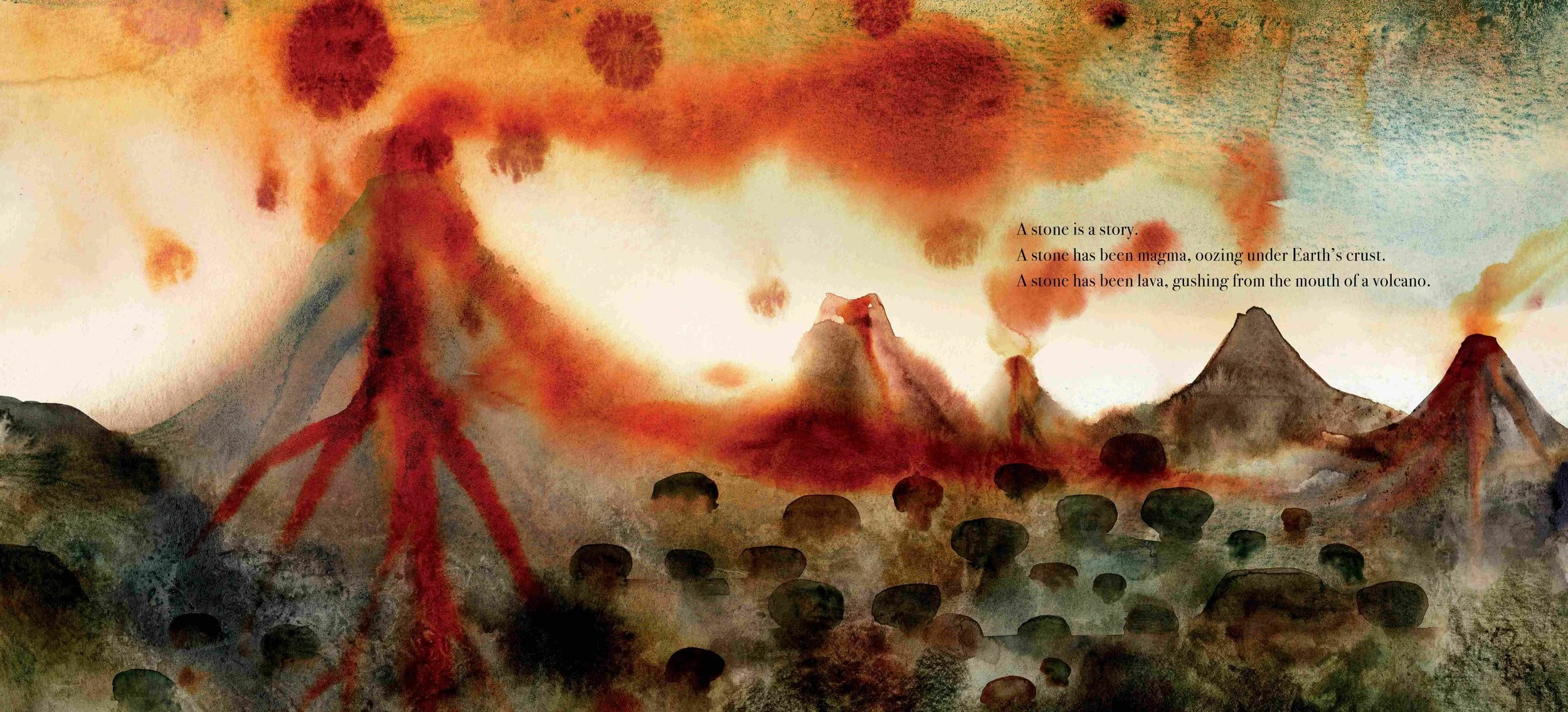

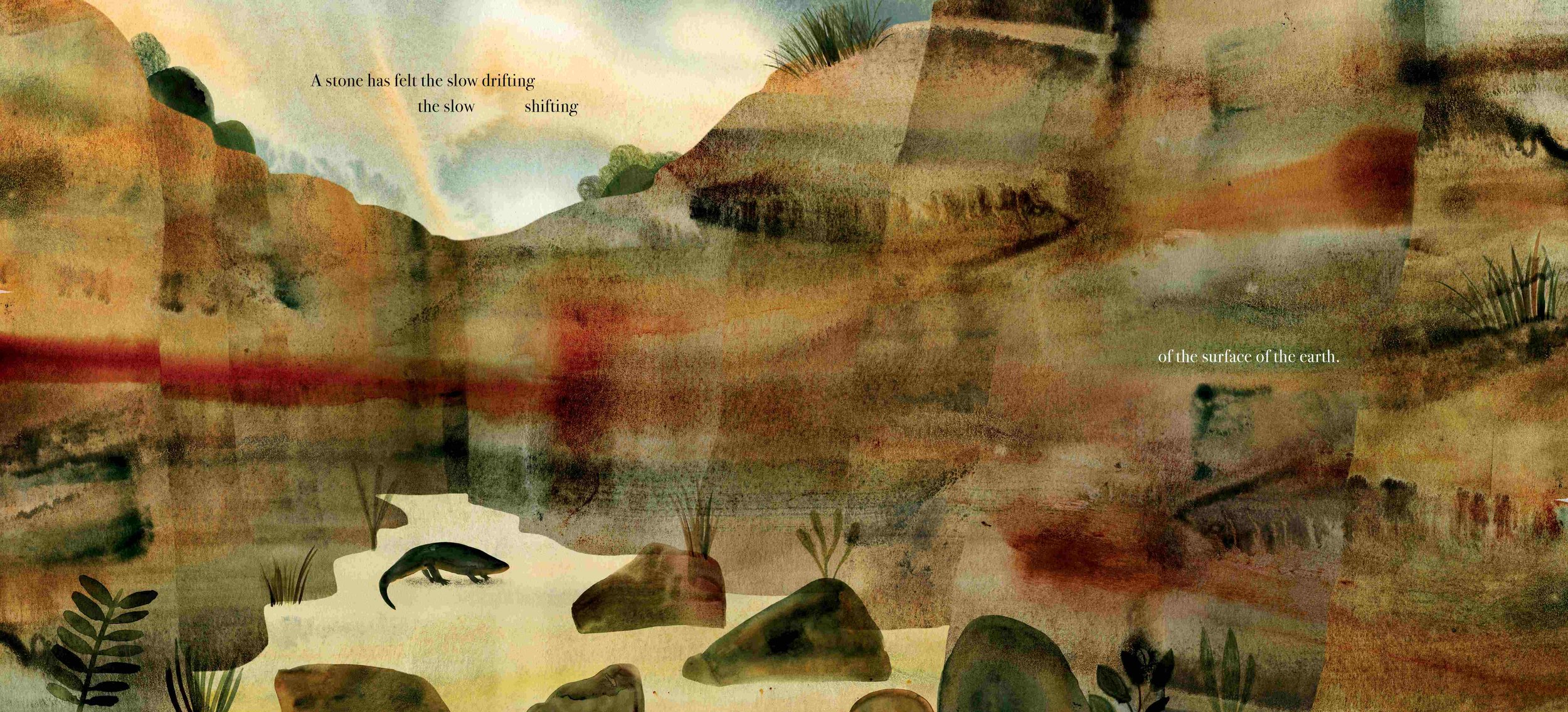

[Leslie] A Stone Is a Story was inspired by a question my daughter asked one evening at dinner: "Where do rocks come from?" This question started a fascinating conversation that continued into the coming weeks. It turns out, stones aren't as simple as they seem, and the more I read about rocks, landscapes, and geology, the more I wanted to know. As I researched the rock cycle, I learned that over long timescales, rocks aren't inert; they are dynamic and ever-changing. So I set out to write a book that follows a rock over hundreds of millions of years as it forms and transforms—becoming an object that can offer insight into Earth's deep past.

The rock cycle engaged me intellectually—how cool is it that natural forces continually shape Earth’s rocks, sculpting them into a tangible record of Earth’s deep past?—but it also sparked an emotional response in me. For me, geology is so much more than facts about rock types. It’s also about transformation, resilience, and the immensity of time. It’s about finding a rock, holding it in your hand, and for a moment being connected to everything that’s come before you, and everything that will come after you. That emotional element—that deeper level of meaning—opened the door to this story, and compelled me to write this book.

{Uma] Did the story show up as a poem, with line breaks and rhythms or did you have to work at that part?

[Leslie] This text showed up as a poem right away. Poetry felt like the perfect vehicle for blending science, emotion, and reflection. I drafted the bones of the poem fairly quickly. Then the real work began! I played with line breaks and rhythms, reading the text aloud to myself over and over again. I wanted it to flow like music—to be singable. If I ever felt the slightest snag or stumble, I sat down again and revised. I'd adjust line breaks to better control pacing and rhythm. I'd notice how words felt in my mouth as I spoke them aloud, and if the sound of a word didn't match the mood of the moment I was portraying—for example a harsh sound expressing a light, airy feeling—I'd find a new word. That part of the process is fun for me—almost like a word game, where the goal is to find "the best words in the best order" (to borrow from Samuel Taylor Coleridge). I also asked fresh readers—including my kids—to read the manuscript out loud to me so I could make sure the pacing and rhythm I intended was actually coming across, and that the "sheet music" I had created with words and white space was legible to others. Because picture books have so few words, and because children respond so strongly to music, I spent a lot of time on sound design as I wrote and revised. I wanted the text to be a transporting sensory experience shared between caregiver and child, and I think the music of the language is vital to achieving that.

[Uma] How did research and facts grow the poetry?

[Leslie] As I researched, I started to have an emotional response to what I was learning—to the fact that a rock's form can reveal its past, and to the fact that rocks are impermanent and ever-changing over long timescales. Once I felt that emotional tug, I knew I had the seed of a story—or better yet, a poem. Poetry seemed like the best fit for conveying the facts of the rock cycle along with the big ideas and emotions that the process had inspired in me. I also had mentor texts in mind, specifically Water Is Water by Miranda Paul and Marion Dane Bauer's The Stuff of Stars, both gorgeous poems about science. I really admired the way these books made complex science topics both accessible and compelling. I reread these books often and used them to better understand what is possible when science and poetry meet.

The more I learned about the rock cycle, the more I couldn't resist sitting down and turning my newfound knowledge into poetry. I had a solid understanding of the topic as I sat down to write the first draft. Of course, as I wrote, more questions surfaced. When they did, I would pause and return to my research, diving deeper into how sedimentary rocks form, for example, or looking up how long trees have existed on Earth to make sure that the trees in A Stone Is a Story appeared at the right time.

[Uma] The Stuff of Stars and Water is Water—I love it when a book is in conversation with other books. But what about the other conversation in picture books, between words and images? Leslie, did anything in the text change once the images were in place?

[Leslie] The text remained the same, though one page turn changed to better fit with the art.

[Uma] Which page was that?

[Leslie] Initially, we'd planned for the text that is now on the 10th spread ("Cave lions have prowled. Mammoths have grazed. The first humans have made the first music.") to be part of the 9th spread, where you now see an image of dinosaurs. We'd planned for the 10th spread to include only the text: "And a stone?" This created a nice sense of pause, a feeling of being on a precipice. But to really show the moment with the cave lions, mammoths, and humans (and to keep them separate from the dinosaurs), we moved the cave lion and mammoth text onto the 10th spread, giving it more space. This allowed Marc to fully explore that moment in Earth's history through the art.

Thank you, Leslie! And thank you for creating a book that seems so simple, yet contains a story of ages.