Universal Rule or Historical Power Grab? Reflections on Show-Don’t-Tell

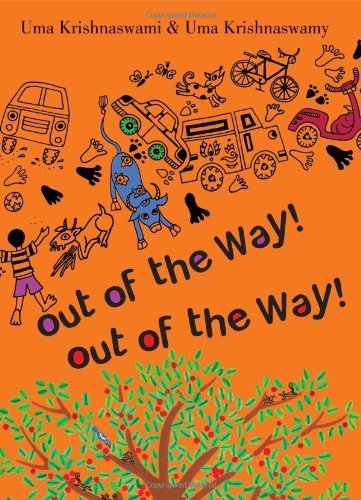

I often tell the story of the publication of my picture book, Out of the Way! Out of the Way! It’s a cautionary tale I was reminded of when I read Namrata Poddar’s pointed, articulate essay in LitHub, “Is ‘Show Don’t Tell a Universal Truth or a Colonial Relic?”

She writes:

As I processed a dominant Euro-American writing pedagogy from the perspective of an aspiring fiction writer and an immigrant critic of color, I couldn’t stop wondering: are we, in 21st-century America, overvaluing a sight-based approach to storytelling? And could this be another case of cultural particularity masquerading itself as universal taste?

In my case, back in the late 2000s, I mulled over the concerns raised by American editors about my picture book story of a boy and a tree. The boy felt passive. The story felt slight. He was a witness in his own story. I tried earnestly to “fix” these problems. I moved the kid to the center of the tale. Gave him a name. Made him take action. Had him speak. Put him in scene after scene. Heightened the conflict. Pretty soon people showed up with axes to chop down the tree. I was buried deep in a story that I could no longer recognize.

On the advice of the editorial team at Tulika Books in India, I threw out the plotty, show-don’t-tell versions. I told the story the way it showed up in my mind, with a long timeline, a single action taken by one young boy, and the place itself as the center of the tale. It became a story about a child in a community, about the power of a single action unleashing a long spiral of consequences. It relies on repetition, on rhythm, on auditory effect, as much as it does on the beautiful illustrations of my almost-namesake, artist Uma Krishnaswamy from Chennai. Picked up by Groundwood Books in Bologna for a Canadian/American edition, it remains in print years after its original publication. It delights me when children pick up the oddity in this book—that the story plays out in repeated circling chants, and even the author and illustrator's names repeat themselves.

Now I’m working on a middle-grade novel and Poddar’s article speaks directly to me. She places orality versus visual storytelling as a political choice, honors digression, the vernacular, and multiple ways of shaping story:

In playing persistently with language, sounds and syntax, multiethnic fiction does not shy away from “writing in scenes,” however, it does dethrone the reign of eyesight to stress the importance of other senses in fiction and hearing in particular.

While I wrote my middle-grade draft, memory and history crept in. The story occasionally steps back in time, adopts one viewpoint, and then another weaves many stories together while keeping the children in focus.

Will it stay exactly this way? Likely not. The written page is not that different from the oral tale in this regard. It changes over time. We recreate it in revision. But Poddar’s essay gives me a helpful way to think about this story. Every story teaches the writer something. This one is teaching me to pay attention to the characters who show up like ghosts and won’t go away, to the rhythms of their speech, and the meaning of repeated actions. It’s seeking the sound of its characters while trying to speak to what Tagore once called “the great meeting of children.”