Process Talk: Karen Krossing on My Street Remembers

In a big-hearted treatment of place and history that feels akin to Australian writer Nadia Wheatley’s iconic picture book, My Place, Karen Krossing’s latest release, My Street Remembers, is grounded in conceptions of people and place that we’d all do well to reflect upon:

everyone is part of history and every place has a story worthy of telling.

story should be told in all its aspects, joyful and sad.

just as the Earth has layers, so do our histories.

if we are to grow beyond our worst instincts, those histories must be told and read and talked about.

I'm delighted to welcome Karen Krossing to Writing With a Broken Tusk.

[Uma] What made you want to write this history through a window that is at once local and as wide as the continent?

[Karen] I experimented with many approaches to drafting this manuscript. Some involved writing about a general street in what is now North America, but the text felt abstract and distant. I also considered writing about a specific well-known street, perhaps one in New York City, or a street where a major historical event had happened. But which street to choose? Narrowing my choices felt daunting.

At the same time, I was deciding on the narrator for this story. I tried out a fictional narrator as well as a collective narrator representing all those who have lived on one street over a long time. I even tried the street as a narrator.

Finally, I envisioned the narrator as a child version of me who was witnessing her collective history of place. That led to a breakthrough: What if I wrote about the street where I live? I dove into my specific street to find the universal story, and I asked readers in the final line: “What does your street remember?”

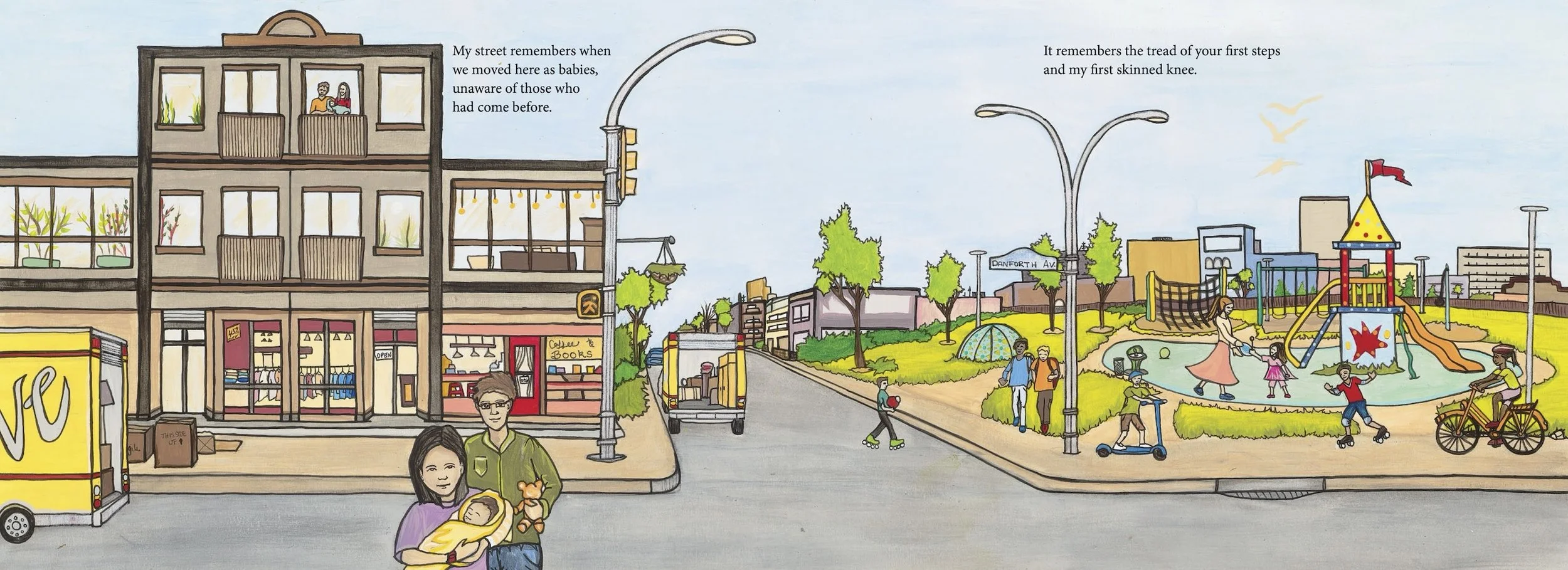

When Cathie Jamieson joined the project as illustrator, we discussed changing to a plural narrator. Cathie has also lived along this specific street, so I could have written the text as “our street remembers” to capture our community experience. Together, we decided against that approach, although Cathie does include a cameo on one spread of both of us as babies, first arriving on our street.

[Uma] Talk about the story turns in this book and how they came to be crafted—the historic wrongs, and the shift from history to the children’s arrival and experience.

[Karen] My Street Remembers begins with the modern-day street to connect to today’s reader. Then it slips back 14,000 years to the end of the last ice age and the migration of Indigenous Peoples into the area. I could have slipped further back in time, yet it would have stretched the timeline thin and allowed for less detail. Also, the movement of Paleo-period hunter-gatherers who followed creatures like mammoths to this land felt like a strong beginning point.

The book then shows the thousands of years of Pre-Contact Indigenous habitation in the Archaic and Woodland periods through mostly wordless spreads. As a White author of settler heritage, I hoped that the absence of words on those pages would be an important act of silence. It would leave more space for Cathie, who is an Anishinabee artist, to illustrate how the Indigenous Peoples lived in harmony with the land for many, many generations. Hours of research lie behind those spreads to accurately depict life during these periods, and there is rich detail in Cathie’s illustrations.

After the Europeans arrive in this place, the story-turns developed naturally by following key historical moments—the 1701 Dish with One Spoon peace agreement among Indigenous Peoples in the region, the 1787 meeting between the Mississauga People and the British about how to share the Mississauga’s Territory, the 1805 meeting where the British forced an unfair treaty on the Mississauga People, the acts of cultural genocide such as banned languages and residential schools, the Black people who were enslaved on this land, and the biases against Irish Catholic newcomers. And the whole time, the land that became my street is changing, getting a new name and joining a new country—one that promised to repair the harm done. I had to select the key moments to portray without overwhelming the story or leaving out important details. I also wanted this specific story to reflect the universal story of streets across North America—to show the harm of colonial practice to this land and to us all. So I needed to keep an eye on how my story would impact a variety of readers from a variety of places.

“The land where we live leaves its mark on us, just as we leave our footprints on it. When we understand and heal our relationship with place, we understand and heal ourselves.”

When the timeline catches up with the modern day again, a wordless spread makes the transition. The publisher and I felt the story needed a beat to breathe and shift, to honour the past harms and the present opportunities for change. We chose a wordless street scene showing a community event acknowledging “Every Child Matters.”

The story’s turns then switch to follow child versions of Cathie and me as we first set foot on our street, grow, and move forward with hope together. I chose these turns to connect back to the child reader.

[Uma] I loved the ending that nudges young readers to think about their streets—there it is again, the local in conversation with the universal. Tell me more about that ending.

[Karen] The ending was difficult to write because I couldn’t just focus on our collective future—our dreams for a better tomorrow—when our collective past contains unhealed wounds and our collective present includes continued harms against Indigenous Peoples. For example, the Canadian government committed to 94 calls to action in 2015 to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance reconciliation, yet only fourteen had been completed as of August 2025, according to Indigenous Watchdog.

For many drafts, I struggled with how to find my ending, until I decided that I didn’t need to provide the answers for readers. I only needed to plant the question for them: How can you deepen your relationship with your street? When the child reader accepts this invitation, they become an active part of future change, just like I have become an agent of change by writing this book.

[Uma] If there’s one thing you’d want young readers to take from this book, what would it be?

[Karen] The land where we live leaves its mark on us, just as we leave our footprints on it. When we understand and heal our relationship with place, we understand and heal ourselves.

Thank you, Karen, for your thoughtful, insightful rendering of humans and our relationship to land, not just in one street representative of your own street in Toronto, but for all those streets that child readers might call their own. This book is deeply Canadian, yet with universal resonance.