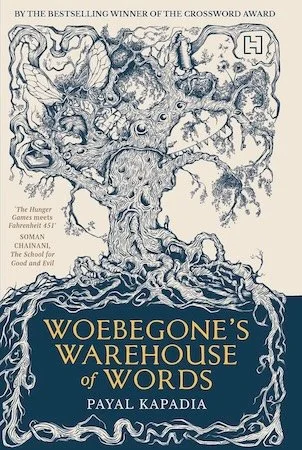

Process Talk: Payal Kapadia on Woebegone’s Warehouse of Words

“Where nothing can be named, nothing is.”

In the tradition of novels that play with words (The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, The Wonderful O by James Thurber, The Neverending Story by Michael Ende) Woebegone’s Warehouse of Words by Payal Kapadia hit me like a—well, like a box of words falling off a warehouse crane. It felt significant to be reading it now in the middle of a time when words are often weaponized and taken away from people in the real world, where words exercise power and judgments are frequently made by the powerful about who ought to use them and when.

Here’s my conversation with my colleague and friend, Payal Kapadia.

[Uma] I have been thinking of how actions taken with good intentions sometimes have unintended horrible consequences (think historical pendulum swings and short public memory). Perhaps that’s why this line, spoken by the prisoner to Zeb, leaped off the page at me: “[E]verything good has within it the possibility of the grotesque don't you think?” So my question is, what's good in the world that made you want to write this book? And what in the real world feels grotesque or threatening that likewise led you to this story?

“All too many dictators started out as do-gooders. All too many monopolists started out as dreamers. There is a tipping point inside each of us. And as history shows us repeatedly, we often lose sight of that tipping point. ”

[Payal] There is so much that is good in this world. Our words have come to us as an undeserved grace, wild and beautiful and unbidden. They are as vital as air, as mysterious as our universe’s most well-kept secrets, as alive as we are. Do we breathe life into our words, I wonder, or do they breathe life into us? My book celebrates this strange and magical bond between human beings and their words.

That joy was tempered, however, by what I sensed, a slow erasure of language. I began to read about language extinction and discovered that 3,000 languages spoken on our planet would be gone by the end of the century. Wiped out. Never to be spoken or heard again. (India, I read, had already lost 220 languages in the last 50 years.) What happens when our words die, I thought. We lose the sensations, the memories, the experiences those words stand for. We lose our connection with our world – and with each other. So I made the Words in my story look like us. They became characters, with fears and dreams, and I wanted my readers to draw closer to them, to care for them.

It wasn’t only language extinction that bothered me. I could not help feeling a sense of unease about the grotesque crowding out the good in other ways, too. Our farms and our factories, our cities and our highways clearing out our forests, taming our rivers. Our comforts and our conveniences, disconnecting us, hardening us. Our leaders turning words into weapons. There was a wistfulness in me for a time “when things grew and weren’t grown”. And yet, everything we call progress comes from a good place, from a well-intentioned desire to sustain humanity. Where did we go wrong?

I believe that the human heart is a conflict zone for the good and the grotesque. Attach an ego to what is good, and it becomes performative, aimed at winning the acclaim of others. It takes on a self-righteous shrillness. It sets out to make the world a better place because it cannot bear to look inward. It becomes delusional. All too many dictators started out as do-gooders. All too many monopolists started out as dreamers. There is a tipping point inside each of us. And as history shows us repeatedly, we often lose sight of that tipping point.

Photo courtesy of Payal Kapadia

[Uma] Asha and Zeb reside in a world of shrinking vocabulary. Can you tell me more about how these characters developed for you?

This is a world where you must buy words to use them. It felt logical for me to picture both Asha and Zeb as two stifled 15-year-olds because their alienation had such an adolescent angst to it. I suppose most teens will relate to this struggle to express yourself and be understood. I thought about what human beings would do in a word-strapped world to cope, to connect, to communicate. I looked at Banksy’s graffiti art – what a cry of protest it is – and that inspired my characterization for Zeb, a boy finding an outlet for his deepest feelings of rebellion and unrest as a graffiti artist. Asha’s characterization drew inspiration from the real-life story of a teenage girl in Anna Funder’s Stasiland. That girl attempted to scale the Berlin wall and was arrested for leafletting. Her courageous revolt had a deep impact on me while I was gestating this book. I began to ask: What does it mean to be a dissenter?

[Uma] What, indeed? I found myself reading the present into your fable. I’m interested in your thoughts about what readers bring to a text and what you would like them to bring to this text.

George Saunders says that ‘the part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world.’ I was writing this book for three years, on-and-off, on-and-off, and everything I read and saw percolated into my writing. The more deeply I got into the book, the more I began to see parallels in real life.

We don’t live in a world where we have to buy words to use them. But there is a price to speak, isn’t there? Modern dictators rule with words and stories, not guns. They know that words have power, that stories have power. They know that a singular word is more dangerous than any other: Truth. No wonder it’s such an endangered thing these days. It can topple tyrants.

And just look at social media: everyone is telling us a story and selling us a story. My imagined world is not really that different from the world we live in.

And yet, I wanted to draw attention to the fact that stories are fragile. They draw their power from our willingness to believe them. And the more we read, the more keenly and deeply we read, the better we get at filtering all these stories that bombard us. To tell between what feels like the truth – and what sounds like a lie. For this is a distinction we must each make for ourselves. In my book, the Words in the warehouse and the Speakers in the city are trapped by a cruel system, but they are also prisoners of their own willingness to believe and to do what they’re told. It’s almost easier to comply, to be blind, than to open one’s eyes and be free.

[Uma] An editor told me years ago that every story has to have a big tomato—an idea that drives the story. What’s your big tomato?

[Payal] The alliterative title of this book has an added significance. The www also stands for the world wide web. We live in a world where every want is met. At the touch of a button. At the click of a mouse. But what happens when you hit a buy button? Who are the invisible people on the other side of it? The Speakers have no other way to speak, and the Words have no other way to be spoken. Both are trapped in a world which is presented as if it were teeming with choices. The truth is, there aren’t any. Woebegone’s Warehouse of Words is about the unseen cost of living in a world short of words that answers your every want but sidesteps your real needs. What are our real needs? I suppose our real needs are to speak, to be spoken of, to connect.

I’ll end with a passage from your novel:

He crawled out of the tunnel at last and lay upon his back, winded, drowning in the blue dome of the sky. A lone bird wheeled, making solitary circles. It could've been the last bird in the world, for all he knew.

He heard Resistance’s voice again. We’ll stay here and catch our breath.

Sometimes you just have to do that. Stop and look and catch your breath. Through its frantic pace and twists of story, Woebegone’s Warehouse of Words leaves us with a breath to catch, a world to become aware of. Thank you, Payal.