Process Talk: Monisha Bajaj on A Year of Kites

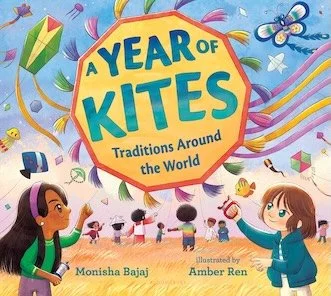

I used to be a clumsy kid, so I have to admit that I never took to kite-flying. It called for more dexterity and coordination than I was ever capable of, but I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of kites, at once tethered and not, splashing the sky with bright color and fluttering movement, riding on the wind. They’re also amazingly poignant symbols of us, humans, our feet on earth and our hearts, yearning. See my post on the Fly With Me Kite Festival. So I was delighted to see the e-galley of A Year of Kites by Monisha Bajaj, illustrated by Amber Ren. Its spreads are filled with the magic of kites in skies around the world. I invited Monisha to talk about the creation of this book.

[Uma] From the jacket text, I gather A Year of Kites began with a pandemic project. Can you tell me more about how a school-at-home lesson on the history of kites turned into this book?

Photo courtesy of Monisha Bajaj

[Monisha] I have been interested in writing for children for a while as a way to simplify some of the academic concepts related to peace and human rights that I’ve spent over two decades researching and teaching on. I was drawn to children’s literature as a way to get these concepts—such as dignity, justice, fairness, equity—to a wider audience and earlier than the students I usually work with who are graduate students in education. I had thought about children’s books ever since I became a parent in 2013 and spent so much time reading books to my kiddo, but I wasn’t sure exactly what I would want to write about or had the expertise to write about until the pandemic.

During the pandemic I went into a rabbit hole after my son had a zoom lesson when he was schooling from home about kites and their origin. I grew up between India and California and I had participated in kite flying in South Asia, as well as have seen various immigrant communities flying kites in California such as through an annual kite festival that used to take place in our city. I began learning about kites in different cultures and got every children’s book I could find on the topic while we were all cooped up at home in the Spring of 2020. I noticed that every book was about a particular festival or tradition in a specific place, but no book talked about these traditions in conversation and across the globe to draw out the unity in diversity regarding kite-making and kite-flying. This book has changed quite a bit from the initial and looking back at it, very bad first draft, but the core nugget of sharing about kite traditions from across the globe is still there from the original idea and spark for this project.

[Uma] I find it both significant and touching that you begin this book with two spreads—one of a girl on a rooftop in India, the next of a boy and his friends in Pakistan, each aspiring to send their kites up into the sky. These are nations at odds in the real world, and you could have opened with any country. Tell me what that opening means to you.

[Monisha] Thank you for pointing this out! I don’t think I had even consciously noticed that the book opens this way. It feels very poignant that it does though because my family is from India and my parents’ families were all refugees from the 1947 Partition so our ancestral homelands are in what is now Pakistan. The character in the India spread is named after my mom, and the character in the Pakistan spread is named after my son. I think subconsciously, these two spreads are the closest to my heart, but the way they open the book came about in a more recent revision. The original draft of the book featured a classroom where kids from different backgrounds shared about their kite traditions in their multicultural families, culminating in a community kite festival; the later revisions of the book morphed into a chronological exploration of kite flying in different moments of the year across the globe. This shift was an idea from my amazing editor Megan Abbate at Bloomsbury to make the book have a common refrain on each page and allow the readers go from one place to another throughout the calendar year and learn about kites. That the two countries—India and Pakistan--share so much in common, yet have been engaged in such violent and tense conflict for the past eight decades, reminds us of why the message of this book is so important: if we can focus on what unites us rather than what divides us, peace is not only possible, it is promised.

[Uma] There’s a glossary in the back matter but it’s possible to read the book all the way through and understand the words you integrate into each spread. Tell me about your weaving of words in many languages into your text.

[Monisha] I am a professor of international and multicultural education with a focus on peace, human rights and migration. When I first started shopping the manuscript around, as a complete newbie with no formal training in how to write picture books and no agent, I kept getting the feedback that I was trying to educate too much and the text was too didactic. I attended classes, sought editing support from different professionals, and benefitted so much from the hands-on editing style of Megan, my editor at Bloomsbury once the book was acquired. From the first draft though, I knew I wanted to include different words from the different cultures and use the book as an educational resource. I wanted readers to hear different sounds and words and to decenter English as the only language in which we can hear concepts and stories. I know children’s book authors have different perspectives on whether to include glossaries or not. For me, I felt that including the original words in different languages for kites and kite-making was important, and that the glossary could be a place where readers—whether children or educators/caregivers—could get more context if they so desired. We even included some Urdu text on the kite image in the Pakistan spread because I also wanted the story to have some surprises/mirrors for readers who might know these languages. My editor Megan also encouraged me to simplify the story for readability and one way to do that was to put more into the backmatter in the author’s note and glossary.

[Uma] The last spread is rhythmic and short, bouyed by a little interior rhyme: "Kites fly high under one vast sky, across the whole world, all year long.” I won’t reveal the final lines but will you talk about how you developed this text, balancing information with read-aloud quality? Unpack your process for me if you will.

As a complete newbie, I’ll admit that this text really transformed for the better in the editing process. I was encouraged in different classes I attended and by editors I worked with to read the book aloud as I edited. This is where the refrain came about and it felt natural to have the core message of the book be included at the end. This is a book about the traditions and hopes that unite us as global citizens on our shared planet. So the final page gives a nod to that. At the end of the day, educating for peace is my life’s work, so anything I write is going to be about that.

[Uma] There’s ample research beneath this simple text. What delighted you as you looked into kites around the world? What surprised you?

[Monisha] Going into a research rabbit hole is part of my training as a scholar and professor. I learned so much over the six years from when I first had the idea for this book! I started with a very rudimentary knowledge of kites. I knew about India’s annual Uttarayan festival, but the traditions I learned about that really delighted me were:

(1) the Matariki festival that Māori people in New Zealand celebrate and the long history of kite-making in Polynesia that dates back thousands of years.

(2) how kites are used in Guatemala to send back visiting ancestors and deceased family members who come to visit during Dia de los Muertos, an annual festival rooted in Indigenous cosmology that sees the dead as very much a part of our living world.

(3) the koi fish kites, symbols of swimming upstream / overcoming obstacles that form part of Japan’s annual Children’s Day celebrations historically. More recently, this has expanded to include celebrating girls alongside boys, who used to be the only ones celebrated in this way.

So many kite traditions have significant meaning and symbolism. What surprised and delighted me was that so many of them involved hopes, communications with gods or ancestors, and future-related predictions and aspirations. Several of the kite flying traditions from distinct regions involved writing something one wishes for, perhaps in secret, or a message to a loved one, and launching it to the sky.

[Uma] Every book teaches a writer something. What did writing this book teach you?

[Monisha] As my first foray into the children’s publishing world, this book has taught me so much and continues to teach me. The book is entirely the result of persistence and good fortune. I think kite flying is like that – you have to be patient as you unspool the string, and catch the right breeze at exactly the right time to launch your kite. I had so many rejections and detours with this book and the way the manuscript made its way onto the desk of an editor who saw a kernel of promise in it was completely the result of serendipity. The final version is almost entirely rewritten from the initial draft and to have an editor with the patience for that was such a gift. I have other manuscripts that I am working on that are requiring a lot of persistence at present, and I’m hoping will also encounter some serendipity. The publishing industry seems to be contracting and I’m not sure where these other stories will land, if anywhere. The main lesson I’ve learned is that we are conduits for certain stories and if they’re meant to be in the world, they’ll make their way there no matter how long it takes (6 years in the case of A YEAR OF KITES) or how circuitous the route is. As I’ve told people about this book, I’ve gotten so many responses of delight and heard about people’s own stories about kites and what they mean to them. Amber Ren’s illustrations are really stunning in this book and I am hopeful that this little picture book that could brings joy, new information, and inspiration to readers young and old. I’m still learning from this project and all the new people it’s bringing me into contact with, including you. THANK YOU for taking the time to engage in this conversation.

Thank you, Monisha, for embracing the world with kites through this book.