The Sill of the World: Where is the Writer in the Text?

As another year begins I find myself thinking of the passage of time, of generations, and of story.

And because I too, have a fond relationship with an ancient Remington Rand typewriter that sits on my shelf (keeping company with Hobson Jobson, a rhyming dictionary, the Monier Williams Sanskrit to English, and Volumes XVI to XX of the OED) such thoughts lead quite naturally to Richard Wilbur’s poem, “The Writer.”

In her room at the prow of the house

Where light breaks, and the windows are tossed with linden,

My daughter is writing a story.

I love to think of the many ways there are for us to position ourselves in the stories we write. Here is the poet, moving from the sound of clacking keys to this reflection:

Young as she is, the stuff

Of her life is a great cargo, and some of it heavy:

And from there to the memory of a starling finding its way into the house, thrashing around while trying desperately to escape, and finally making it, “clearing the sill of the world.” It’s one of those poems that thickens with each reading, or maybe it’s just that I read it every few years so that I am the one who has managed to slow down sufficiently to see beneath the poem’s surface.

“A good riot needs something upon which it can hang its righteous hat...”

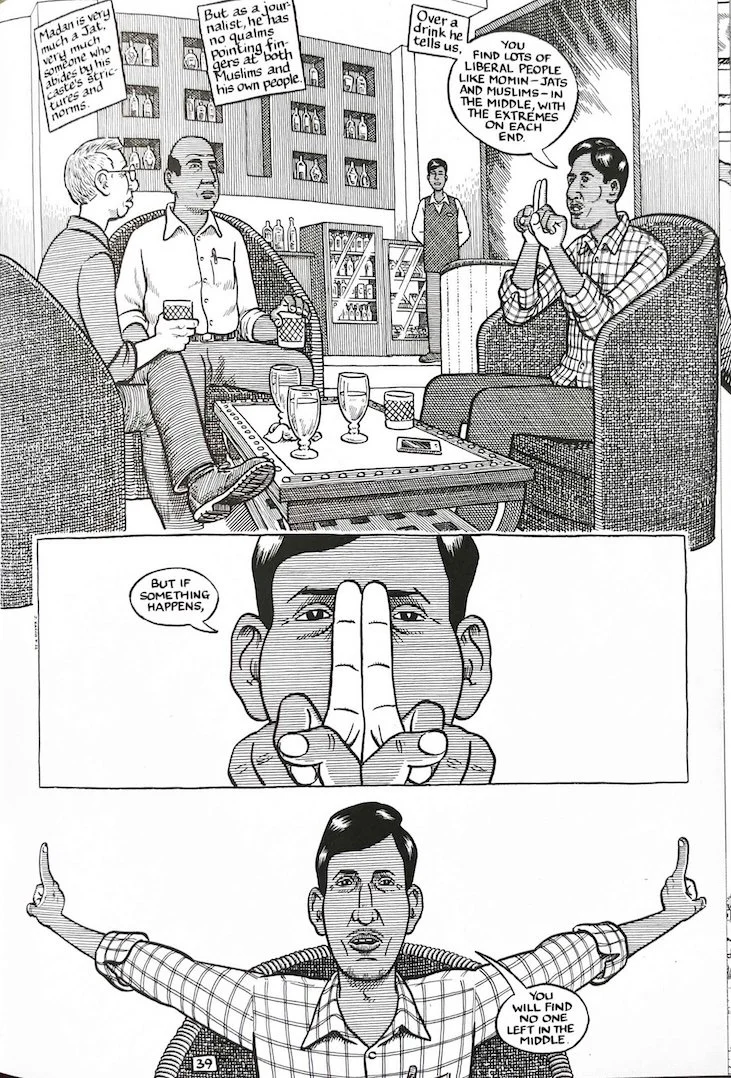

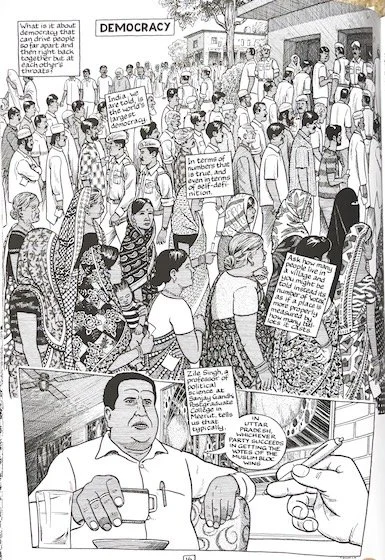

Like the poet writing from within the poem’s sensory impressions, Joe Sacco, a Maltese American cartoonist who pretty much invented the form referred to as comics journalism, locates himself within the framework of his reporting. In The Once and Future Riot, Sacco immerses himself in the Muzaffarnager riots of 2013, when Hindus and Muslims in a small town in northern India, riled up by rumours and circulating vitriol, turned on one another.

Sacco has created comparable works set in Palestine, Bosnia, Gaza, and Canada’s Northwest Territories, employing a trademark combination of journalism and incisive cartoon art. Dedicated to “the hardworking rural journalists of India,” The Once and Future Riot is an unflinching look at the slippery trajectory of sectarian hatred in modern India. “Perhaps,” the implied narrator reflects while a driver bumps him and his team over a pothole-riddled road, “we’ve been getting too far ahead of ourselves.” In the very next frame, he writes:

“A good riot needs something upon which it can hang its righteous hat, some specific outrage at some specific time and place to serve as the first definitive marker on the road to no return.”

Pages from The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco

In the world’s largest democracy, disinformation and rumours tip into violence. Sacco delves into longstanding political history as well as caste and class relationships that mediate the politics of today. Some of it is clearly intended for readers who know little of the region, but other frames, dense with the events of the recent past, lead us through opinions and speculation and conspiracy theories that in turn culminate in violence. Through it all, Sacco’s journalistic voice appears in frames that offer commentary. This is more than a device—it’s the medium of the message. It ties together the unfolding riot seen from many perspctives, including that of local journalists, who endure serious consequences while trying to find and report on the truth. That author self, present throughout, shows us how reason and dialogue get jettisoned in the lead-up to riots.

In the end, that is the voice that leaves us with a sense of what this means for the rest of the world. Specific outrages may pass and even be forgotten in the longer term, but how shall we rid ourselves of the hatreds that endure? That is the sill of the world on which we must position our reading selves.

What I’m drawing from this is also that every writer needs such a sill. We create it by asking, What am I trying to say? What is this narrative I have on my hands?

Julian Brave NoiseCat (Secwépemc)* finds different sills to perch upon as the teller of a blend of memoir, history, and traditional Indigenous tales. The result is his book, We Survived the Night, a glorious melding of then and now, historical and present, personal and political. It pulls apart the threads mythologizing both America and Canada. It hops nimbly across the borders between them, showing us how the laws of both nations draw on a couple of centuries of intentional erasure, locking past and present in a deadly embrace. From the breathtaking opening that tells of his father’s near-death as an infant, we are aware of the teller whose breath has made this narrative.

Look at this passage from Chapter 2:

Salish languages are what linguists call agglutinative. Which means speakers make words by combining morphemes—linguistic units of meaning—into words and phrases. Fluent Salish speakers are, in this sense, constantly making words.

“...we were reminding ourselves and our children how easy it is for things to fall out of balance, for our bellies to turn ravenous, and for the good life to be lost.”

Reading along, I glimpse the intricacy of a language and the complications of its speakers and I also feel invited to stumble over its words. I am an outsider and that is okay. Then the next paragraph artfully catches me off guard.

Salish languages have been studied extensively by linguists because of their challenging phonology, which is likely evident in your attempt to sound out the Secwepemctsín words I've used in these pages.

Ha! Yes, this is about memory and story but it’s also about me, about my preconceptions and about opening my mind. Here’s that nudge again, in a chapter titled “Custer Died for Your Sins:”

So every winter when the Coyote People came together to tell Coyote stories, we were reminding ourselves and our children how easy it is for things to fall out of balance, for our bellies to turn ravenous, and for the good life to be lost.

And isn't that exactly what modern humans have done? Things have fallen grievously out of balance and the good life, where it existed, is being lost. NoiseCat makes human and humane things like the tragedy of the commons that we generally talk about in platitudes if we talk about them at all.

One thing he does particularly well is the framing of history as tragicomedy, shorn of the victor’s asserted virtues. The Vikings in Greenland, the journey of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, the arrival of Christianity, the naming of the Fraser River, the competing myths around the “disappearance” of the Roanoke colonists—these are just some of the events of which we’re offered funny, succinct summaries. It’s a wonderful departure from histories that are typically narrated in terms of racial superiority having prevailed. I was particularly delighted by the account of Mary Simon (Inuk), Canada’s current Governor General, and the first Indigenous person to occupy that role. And maybe it was my years in New Mexico that made me feel all weepy at the description of two Native American women, Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) and Sharice Davids (Ho-Chunk) taking their oaths on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives in 2018. A reminder that even when things are out of balance, every step toward survival counts.

Through all of this runs the writer’s personal narrative of families broken and mended, wandering and reconnecting. Even the notes at the end of the book contain lines that made me want to cheer:

It is the height of colonial hubris to claim that the important works of the humanities all come from so-called Western civilization.

There are so many ways, NoiseCat seems to be saying, to be all things human—angry and forgiving, petty and generous, and above all aware of the laughter of those who have survived against terrible odds.

This reading and writing year, 2026, is open wide. I’m going to try and remain alert to how the writers I read place themselves into their stories, how I might place my own writer’s soul into the pages I’m trying to craft.

*See as well Julian Brave NoiseCat’s Oscar-nominated documentary, Sugarcane.