Guest Post: Rowena Rae on Why We Need Vaccines

I met Rowena Rae when our books were both shortlisted for the 2025 City of Victoria Children’s Book Prize. That unexpected recognition (for me anyway!) brought us together — it’s the kind of writerly connection that feels like a gift.

We all come to this children’s writing gig along vastly different paths. Rowena worked as a biologist in Canada and New Zealand before becoming a freelance writer and editor and a children’s author. Like me, she lives in Victoria, British Columbia. We share a sense of perspective lent by a little mountain that used to be called Mount Douglas and has now officially embraced its SENĆOŦEN (Saanich language) name, PKOLS. I love that the Indigenous name has slipped gracefully into public nomenclature. The mountain is a defining geographical feature of this city that Rowena and I both call home.

Rowena’s shortlisted book is Why We Need Vaccines: How Humans Beat Infectious Diseases, illustrated by Paige Stampatori. I asked Rowena to tell me more about the creation of her information-packed book for young readers. She wrote about finding a source she could easily have missed, and the process of collaboration with the illustrator.

Photo courtesy of Rowena Rae

When I was starting the research for my most recent nonfiction middle grade book, Why We Need Vaccines: How Humans Beat Infectious Diseases, I came across a thin paperback at the library. I nearly missed it, stuck as it was between two volumes with wide, heavy spines. It was called The Vaccination Picture, written by Timothy Caulfield and illustrated by numerous artists, among them the author’s brother, Sean Caulfield. The Vaccination Picture fascinated me, not just because it was about the topic I was interested in, but because of its bold mixture of writing, artwork and design elements. The art is colourful and varied, and the presentation of text alongside the art is striking. The result clearly showed the collaborative effort involved.

“Editors’ work so often goes unrecognized, yet it’s critical to preparing a book. ”

All books are collaborations, but so frequently many of the players are invisible. Collaboration is one of my favourite parts of writing a book, so later, when my proposal was accepted by Orca Book Publishers, I was thrilled that they wanted to include the finished book in an illustrated series called Orca Timeline. I had never worked with an illustrator on a nonfiction book, but I was excited at the prospect.

Illustration ©Paige Stampatori

I was paired with an Ontario-based illustrator, Paige Stampatori, whose work is bold and colourful, with a touch of whimsy. Paige’s portfolio at the time included many illustrations for nursing magazines and other healthcare clients, and this reassured me that her work would complement my text about vaccine history, science, ethics and social issues. And complement it does—beautifully. Paige’s illustrations provide some levity to the seriousness of the book’s content, and they also make some fun connections. One of my favourite illustrations is of a syringe in the shape of a cow, at the place in the text where I explain how a dairy farmer made the link between dairy workers exposed to a virus called cowpox and their immunity to the smallpox virus. This connection led to the world’s first vaccinations.

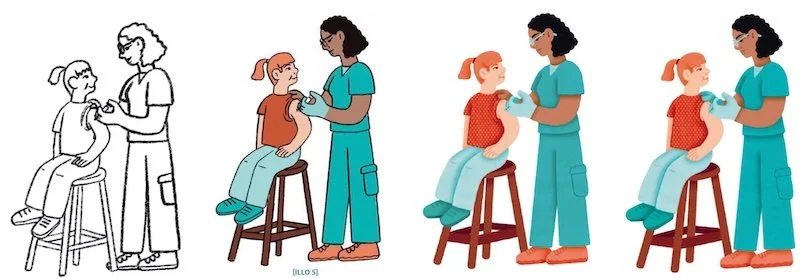

Illustration © Paige Stampatori

My editor and the book designer at Orca mediated the exchanges between Paige and me. First I was given brief descriptions of each illustration and information about where it would be placed relative to my text. Then came black-and-white sketches in the page layout, and next I saw more detailed illustrations with colour. Last I received the pages with the refined colour artwork. Throughout, I had the opportunity to comment and request tweaks, which I did only when historical or scientific accuracy was needed. For example, in a chapter where I talked about the history of various infectious diseases, I mentioned the 1918 flu pandemic that swept much of the world as soldiers and others were returning from World War I battlefields. Paige illustrated a soldier, and we worked with photo references to depict the uniform correctly. In another illustration, a nurse is immunizing a young girl and initially wore a medical glove on only one hand. Over the course of the illustration development, I asked for both hands to be gloved.

While working with Paige on the illustrations was a new experience for me, working with my editors, Kirstie Hudson and Vivian Sinclair, on the text was not. Kirstie and I went back and forth with the full manuscript three times, during which Kirstie helped me tighten some wordy passages, better explain some of the complicated science, and adjust my language where I tended to write at a higher reading level than my audience would likely understand. After Kirstie’s work, Vivian copy edited the text to improve the flow of many of my sentences and catch my grammar and punctuation mistakes. Editors’ work so often goes unrecognized, yet it’s critical to preparing a book.

With the text polished and the illustrations underway, book designer Dahlia Yuen worked on the overall presentation of the book. She had laid out all the basic elements—titles, headings, fact boxes, sidebars—early on so that Paige knew how much space was available for the illustrations. Dahlia also found and placed photos and designed charts and other graphics that I was keen to include so readers could view information in other ways than just text. As each mock-up of the pages came to me to review, more and more details appeared, such as fonts, colours, and watermark designs. Over many months, the book evolved into the final product—my text polished by Kirstie and Vivian, Paige’s illustrations, and Dahlia’s design magic. A true collaborative effort.