Guest Post: William Alexander on Sunward

When I taught at VCFA, I had the pleasure of serving on faculty with plenty of smart, informed, talented writers. Among them was William Alexander. Will is the author of Goblin Secrets (a National Book Award winner), Nomad, A Properly Unhaunted Place, and other novels, as well as chapter books both fiction and non.

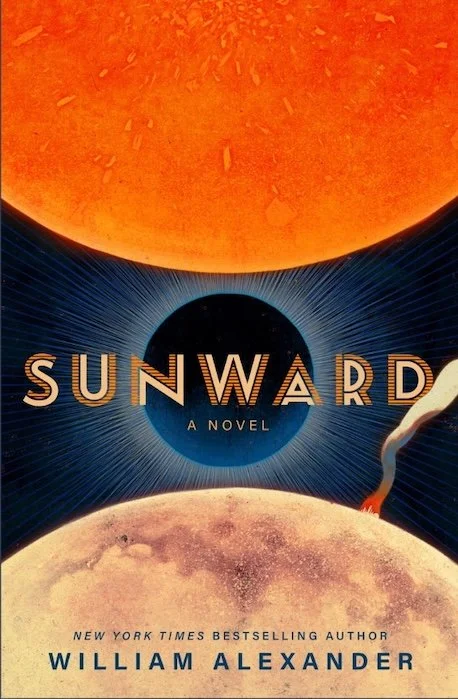

Now he’s written a book for grownups, Sunward, in which the protagonist, Tova Lir, is a planetary courier responsible for training adolescent androids. Is this space opera, or cozy sci-fi? Maybe it’s both. In the world of Sunward, robotic kids need care, nurturing, raising, much like human kids. The novel is set in a solar system racked by interplanetary conflict in the wake of an explosion on Earth’s moon. In the best sci-fi tradition, this is at once our world, and not.

Allow me a brief digression. This blog, Writing With a Broken Tusk, is named for a boy who was made, not born. That’s the essence of the origin story (over a thousand years old) of Ganesha/Ganesh, the elephant headed god of Hindu tradition. The goddess Parvati made him—from earth, in some tellings and in others, from dirt and/or skin cells sloughed off her own body. A post about a book that deals with raising robotic foster children felt like a good fit here.

In Sunward, fiction creates dynamic possibilities out of the dismal future projections that inundate us. It also contains implications for real children. Thank you, Will, for indulging me and writing this guest post for WWBT.

Let Them Be Magnificently Different

by William Alexander

“We’ve been telling stories about artificial children for centuries.”

I usually write for kids, but in Sunward I wrote about them instead. My own experience of pandemic parenting, with its strange mix of homebound cosiness and quarantined dread, set the tone for the book. My protagonist, Tova Lir, muses about generational tensions while trying to protect her robotic foster children: "Meat vs. metal. Parents afraid of getting displaced by their kids. Old gods trying to swallow all the new ones. But maybe it's not the only story that we know how to tell."

We've been telling stories about artificial children for centuries. Samuel Butler panicked about the possibility in his 1863 editorial "Darwin Among the Machines."Pinocchio and Frankensteinboth poked at the differences between offspring born and made. Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy was created to replace a human child and became a hero instead. Ted Chiang argues in The Lifecycle of Software Objects that artificial people must be fostered from infancy, slowly and with care; a functionally intelligent being will never spring fully-formed from our hard-drives. (The novella is out of print, but you can find it in his collection Exhalation).

Composite image featuring screenshots of eponymous characters from Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio and Frankenstein, Tezuka's Astro Boy standing heroically beneath a spotlight, and illustrations by Christian Pearce for the Subterranean Press edition of Chiang's Software Objects. Image source: William Alexander

Robotic kids also embody ancient worries about changelings, demon-spawn, and demigods.What happens when our children turn out to be unfathomably different from ourselves?

The actual kids of the current moment are growing up in circumstances that we never could have imagined at their age—even those of us who read lots of science fiction. (SF tends to be about the present rather than the future in much the same way that historical fiction is about the present rather than the past.) The kids are creating new strategies for navigating uncertainty, inventing new languages to describe it, and choosing new pronouns for themselves—all of which is something to celebrate rather than fret about.

Protect the kids.

Let them be magnificently different.

PS - Note that a science fictional celebration of artificial intelligence is absolutely not an endorsement of AI in its current form; LLMs are extractive, exploitative, hallucinatory, brain-damaging mediocrity-machines built on egregious theft and their continued use will scorch the land and boil the seas—unless we can remember how to tell other sorts of stories.

“Unfathomably different from ourselves.” Is there a parent who hasn't felt at some point—their child’s toddlerhood or teenage, perhaps—the unfathomability of the next generation? There’s something generous and inviting about Sunward—Library Journal describes it as “cozy science fiction.”

Maybe it’s the affection with which the narrative depicts the young robot Agatha von Sparkle:

She bounced off every wall on her way to the airlock.

Maybe it’s that the story embraces the moment we’re in, considers its risk and contradictions, then offers readers an imaginative rocket-thrust into the future. It suggests that telling “other sorts of stories” is more than entertainment. Maybe it’s essential to our survival.