Process Talk: Mitali Perkins on The Golden Necklace

Mitali Perkins has been my fellow traveler on the long road of writing books for young readers with the specific aim of crossing cultural and geographical boundaries. In 2017, her novel, You Bring the Distant Near, was a National Book Award nominee. Her Rickshaw Girl won the Jane Addams Book Award. And I can think back to years ago, when I came across her first novel, The Sunita Experiment. It gave me courage to write the stories that were nagging at me.

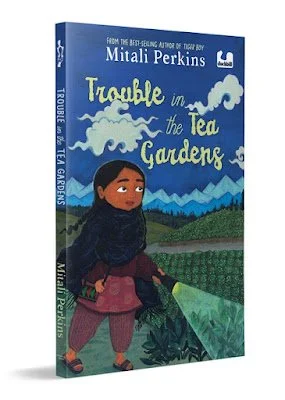

Now, Mitali’s upper elementary novel, The Golden Necklace: A Darjeeling Tea Mystery, like my Book Uncle trilogy, has been published in the US and in India (the Indian title is Trouble in the Tea Gardens). I’m delighted to welcome Mitali to Writing With a Broken Tusk.

[Uma] Let’s talk about setting in The Golden Necklace. Here’s a sentence that made it come alive for me:

“Pluckers handed down their dilapidated plantation owned homes and low paying jobs to their children as if they were gold.”

This is a setting that is beautiful, and it's also oppressive. How did you bring the place and its people to life?

[Mitali] I was born in Kolkata, and Darjeeling is the hill station in Bengal that the Brits used to go to. My family often went to Darjeeling and spent time there, but we went as tourists. And of course, you know the advertisements—the beautiful hands of the tea pluckers and Darjeeling tea being the champagne of teas. You can go there and see these women with the baskets on their heads, bending and plucking. They're Nepali women and they’re beautiful—they have smiles that can light up a room.

I've always been curious to learn more about their lives. When I started delving into their situation in Darjeeling…well, let’s just say for those of us who come in, book the hotels and stay there, it's a whole different experience than the lives of the different ethnic, cultural, and linguistic groups of people who live there. The shortage of water, for example—it just defines them. And they're in a sort of a generational trap, to stay and keep plucking for the same tea estates. All that goes back to the days of the Raj, and Bengalis have continued that. What’s interesting to me is that Bengalis are the oppressors—and I'm Bengali. So I really had to delve into what Bengal has done to that region and how hard it is to be of Nepali descent there.

[Uma] And what did the research involve?

[Mitali] I found a professor at Cornell who had done a lot of work on this. She wrote a book on labor, and especially women's labor in the tea estates. I started by reading her book and then I contacted her and asked her my questions. Charlesbridge was good enough to give her a fee, so we were really able to dig in. She had lived in the area for 20 years and learned so much about the place and people. So that's where I started.

And then, of course, I read widely, and I went to Nepal. I have diplomatic friends who live in Nepal and they were kind enough to host me. I was surprised by how much Nepali I could understand.

[Uma] I found that too when my husband and I hiked in Nepal. So much overlap between South Asian languages.

[Mitali] Yes, I was interested in the overlap between the cultures. I did some linguistic research about how the languages spread and some of the things they had in common. I really love research and I know you do too. It's one of the best things about writing a book like this. You learn so much about a region that you didn't know and about an industry that you didn't know. I’ve studied political science and public policy, so I have always had a bent toward research and understanding, especially systems where language and culture result in oppression. Microcultures within cultures and how people navigate the borders between them—those dynamics have always appealed to me.

[Uma] But to distill all that for young readers, that's always the challenge, right?

[Mitali] It’s challenging, but you know what's interesting? The book is released simultaneously in India and in the United States.

[Uma] That’s very satisfying, isn’t it?

[Mitali] I'm happy about that, because, you know, having immigrated here when I was seven, I have wondered, are my sensibilities really Indian? Does my book still resonate in India? And so when I see that it does, it's a thrill. Indians understand the nuances, that there are different languages and ethnicities and religions within India. Here in the States, you know, you still get questions like, “Hey, do you speak Indian?”

[Uma] I know, sometimes we come up against a rather monolithic perception of places and people elsewhere. Tell me more about using complicated, seemingly unsolvable, real world problems as backdrop and context for Sona's story.

[Mitali] I like writing about that. I like setting my stories in as particular a socioeconomic and political and historical moment as I can. Then those things almost become like a secondary character that you have to know. You have to understand how each interaction plays out. For example, when Sona’s standing in line for water and she's got a Tibetan girl in front of her. What’s their interaction going to be like? The sociultural, economic context becomes another very interesting character that will shape every scene.

I think everybody needs to do that work, even if you're writing about suburban California. What's it like to be, you know, Latinx here or Asian? There are so many different nuances in every situation. That’s why economic, social, political situations are always preeminent in my books.

[Uma] Can you talk about class and class divisions that run through this? Because that seems to be a really important layer of this story.

[Mitali] I think Americans tend to think literally in black and white when it comes to race. The idea of language or cultural nuances leading to class differences that also lead to power differentials—that is not necessarily as easy to see here. People will sometimes think that [if] you're white, you have privilege. But that's not always the case. Class is less visible, when we tend to look at race.

And what is race after all? It's a social construct. Then we might look at culture, and the nuances of cultures that show up in microcultures. What am I? I'm Bengali American. My sons though, they see themselves as Indian American, so they’ve lost that specific nuance. But I find the power differentials really interesting.

[Uma] So did the power structures here come out of the characters or did the characters come out of the power structures as you were trying to write this story?

[Mitali] That's a good question. Sona had to be Nepali because she was a tea plucker's daughter. I think 99.9% of them are women of Nepali origin, even though they've been there for generations. I think that Sona’s character came first, then her ethnicity. Tara being Bengali, I could understand her situation more from my own perspective, my understanding of Bengali culture. That made me want to write across those cultural divides.

I feel like Sona's superpower is her multilingual ability. It's the fact that she willingly dives into languages. As her brother points out, she’s good with languages; she learns them fast. Not brilliantly, in a scholarly way, but to relate to others. That's her skill. That's what leads her to solve the mysteries she comes across. Kids who are bilingual, multilingual, don't realize what a gift it is to be able to speak more than one language. If you can make someone feel honored and respected in three languages, you have a lot of clout. You can go a long way to reverse divisions in the world.

[Uma] Can we talk about Kaki? I found her to be a really interesting character. Somebody who's, you know, trying to break through those structures and demand their rights. A woman who’s tough and doesn't give up, doesn’t care about being likeable, even.

[Mitali] Well, you and I are both getting to be of a certain vintage where we know that being nice is not the point, especially when you're representing other people with less power. You want to have a strong voice and you don't care, really, about being liked as much as you do about justice and fairness. I liked Kaki from the start because she was representing her people, her women, and she didn't care how others felt about her. She just wanted the tea pluckers to get their bonuses, their wage, whatever was promised them. You need that kind of strong leader. She loves Sona’s mom and she loves Sona and she wants the best for everyone. But sometimes that doesn't look like a maternal kind of cuddly figure. She was a fun character to write. I have to say that all my characters are parts of me, and that's definitely a part that's emerged for me in the last ten years.

[Uma] Every character’s a part of you? That’s a writerly truism, isn’t it? But what does it mean for you, for this book?

[Mitali] You don’t have siblings, but there’s a whole world of relationships among siblings. When I think of my siblings, I know I would go to bat for them anytime they needed it. So that's part of Sona’s bond with her brother. Also, I had a brother before I was born, and we never spoke of his name at home. He died before the age of one but we never even heard his name. It was a secret because it was so painful for my parents. But I got to this place with my dad, toward the end of his life, when he was opening up more. So I asked him, what was the name of our brother? He told me that it was Shamiran, which means a breeze, a gentle breeze. And I thought, this would be a good character name for Sona’s brother, a way to bring home my own lost brother.

[Uma] Mitali, that is so touching.

[Mitali] A brother that I would have loved to have, but never got to have.

Otherwise, Sona and her ability to play with the language and words, her desire to see justice done, her desire to care for her parents. Those are all things I had at her age. There are actions she takes that I didn't, but I'm trying to take them now. These are her small acts of generosity, like with her water supply. Each time she chooses to share the water—this limited amount of water that she works hard to gather—the mystery gets more accessible to her. So I've played around a little bit with her as an aspirational character for me, personally.

[Uma] Which brings me to the mystery. Did you always know that this was going be a mystery?

[Mitali] No. Well, okay. It started as a short story for a Canadian Advent calendar. One story. I just wrote it for fun, and when they were looking for submissions through my agent, I sent it in. There was a bit of a mystery in that version as well, but she finds the gold hidden in a tree because she's a tree climber. I knew somehow from making up that story that it was going to be her strength, some unique strength, that would lead to the solving of the mystery. But then as I began to write it as a novel, it became more complex and the mystery took on more substance.

[Uma] Of course, once you get into the story and it branches in its own way, you have to deal with that, don’t you?

[Mitali] Isn't that exciting, when it takes a life of its own? When the story kind of leads you forward? It is a mystery all its own, that co-creative process with the work itself.

[Uma] Tell me about the dog. When we hiked in Nepal, that was the first time I had ever heard of Kukur Tihar. And it was so cool to go through these villages and see all the dogs wearing marigold garlands around their necks and find out it was part of Diwali celebrations. I was fascinated.

[Mitali] I don't know where that fell off in India because Indians don't have that great a relationship with dogs. But in Nepal, they love dogs. They venerate them, especially during this festival. I told you about my friend in Nepal—her husband is a diplomat. Well, they have a ginormous golden doodle, and this dog is clearly also a diplomat. Nepali people just loved this huge, abnormally large golden doodle. He is a friend everywhere he goes and he makes friends for my friend. I was there for Kukur Tihar, so as the book took shape, it was really important for me to give Sona a dog.

[Uma] I've never liked the plotting-or-pantsing characterizations of writing process, so let's try a different one. To borrow terminology from my friend and writing colleague Mahtab Narasimhan, would you say you’re an architect of story or a gardener?

[Mitali] I would say I'm getting to the point now where the story itself is the architect, and the story itself is the gardener. I just sort of receive it, because it does mysteriously unfold for me now more than it used to. It seems to emerge from hiding as if it’s coming from under the waterline of my brain. I guess it's more like a wildflower meadow now than it used to be in that I’ve been strewing seeds for years now. As I focus on a story, I begin to see what comes up. Not that I don’t use structure or tools that make me think of structure. Save the Cat Writes a Novel, or the hero’s journey—I want my character to forge a pathway, to stumble into the darkest moment. But they’re all tools. The story comes from within.

[Uma] Thank you, Mitali, for sharing your time and insights and congratulations on your lovely book.